A Completely Unmanageable Pile of Horse Sh*t

The unlikely origins of alternative proteins.

"Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?" he asked.

"Begin at the beginning," the King said gravely.Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Where should we start, then?

The Turn of the Century

No, not that one—I mean the turn of the 20th century.

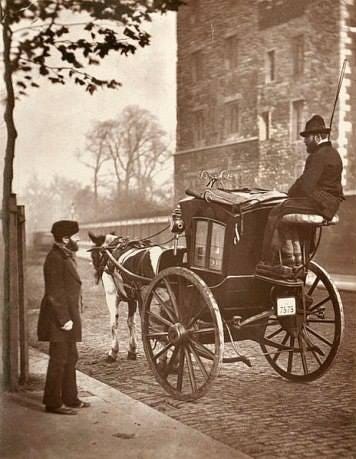

In 1894, a publication in The Times estimated that nine feet of horse manure would bury London by 1950 due to the booming population. The article incited a mass panic, with the crux of the issue being the increasing number of horses (and consequently, the enormous amount of horse manure) needed to transport people and products. Moreover, these tens of thousands of horses would require many acres of land and massive amounts of agricultural feed, but people especially feared the stinking, ever-expanding piles of manure that would cover the city.

The average horse produces between 15 and 35 pounds of manure per day. London alone had 50,000 horses for shipping and transportation in 1900. That’s anywhere from 750,000 to 1.75 million pounds of horse manure every day, just in one city.

Four years after the article’s release, dozens of international leaders, public officials, and urban planners convened in New York to discuss solutions for supporting this rapid urbanization (and preventing the accumulation of horse manure) over ten days. Overwhelmed and intimidated, officials abandoned the effort after only three days of discussion; they could not see an outcome in which we solved the problem; humanity would simply cease to exist in 50 years.

In a 2004 article, economist Stephen Davies coined this event, “The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894.”

And yet, 50 years later, civilization continued to thrive. London even avoided the predicted nine-foot pile of horse manure—the automobile soon phased out any need for the horse-and-buggy.

Why Are We Talking About Horse Manure?

Great question. As an alternative protein scientist, it’s important in my presentations, writings, and conversations to convince people why alternative proteins matter and a big reason is sustainability. In 100, 500, or 10,000 years, we can’t expect that agriculture will be exactly the same as it is now. Our current agricultural practices are unsustainable; we have a finite amount of arable land, but our economic system is built on the assumption that we have infinite resources. We don’t have enough food, water, energy, and land to support our growing population. Changes will be necessary, like diversifying our food supply with alternative proteins.

The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894 has become a popular example of demonstrating how a simple invention (the automobile) can solve a seemingly impossible problem (a gigantic, stinking pile of horse manure). We’re approaching a similar crisis in agriculture. Many journalists, policymakers, scientists, entrepreneurs, and just plain ol’ people are stressed about the fragility of our global food supply, and if we expect to exist a few hundred years from now, we need serious, large-scale innovation. We need the food version of the Ford Pinto (without the spontaneous combustion, of course) to save us from that pile of poop.

This is where alternative proteins come in. What food technologies are radical enough to revive our food system? Proteins that are produced in a fundamentally different fashion than conventional animal protein can help us build a more climate-friendly food supply. Cell-cultivated proteins like Vow’s cultivated foie gras, microbial proteins like Quorn and Spirulina, plant-based proteins like Impossible Meat, and other alternatives can be our Ford Pinto (again, no exploding, I promise!).

Churchill’s Prediction

Three decades after that failed urban planning conference, former UK prime minister Winston Churchill published a short essay titled “Fifty Years Hence,” detailing his vision for humanity 50 years from its time of writing in 19311.

In his essay, he focuses on humanity’s major technological advancements and details how they will undoubtedly enhance the quality of life. Here, I focus on his predictions about food:

“Microbes…will be fostered and made to work under controlled conditions, just as yeast is now….We shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing, by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium. Synthetic food will, of course, also be used in the future. The new foods will be practically indistinguishable from the natural products from the outset, and any changes will be so gradual as to escape observation.”

He rightly mentions that microbial fermentation will become more precise and tunable in future society. Fermentation is the process that microbes (mostly bacteria and fungi) use to chemically break down sources of energy (like sugar) so they can grow and reproduce. In the process, they release byproducts like alcohol and carbon dioxide, which give rise to the characteristic flavors in beer, wine, kombucha, cheese, and more.

At the time of Churchill’s writing, scientists were just beginning to understand the mechanisms of yeast fermentation in wine, dairy, and brewing; just two years before this essay was published, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to two scientists studying biochemical reactions in yeast. Fermentation was an emerging technology that many people felt was a necessary research endeavor.

Now, fermentation has become an essential pillar of our food and healthcare systems. Beyond beer and wine, we harness microbial fermentation to produce insulin, food pigments and dyes, chocolate, cheese, soy sauce, vitamin B12, and emerging alternative proteins like chicken-free egg protein, cow-free milk, and even infant formula. The important distinction here is we have figured out how to precisely control fermentation over the last century. Humans have always, always fermented beer and wine, but for 99% of our history, those fermentations were uncontrolled and the resulting product taste was somewhat random. Now, we can produce targeted products and flavors, which is safer and cheaper!

Churchill also managed to predict our consumption of meat grown without raising a full chicken or cow. Animal farming is calorically inefficient; the average chicken requires 9 calories of energy input to produce only 1 calorie of chicken meat (and chickens are even regarded as the most efficient energy converters in the animal world). That’s a lot of lost energy! If we could produce the same amount of chicken, beef, pork, fish—whatever you like—with greater energy efficiency, we’d have more available land AND more protein to feed our population.

(I’m not going to touch on Churchill’s comment about synthetic food—I’ll leave it as an exercise for you lovely Trash Talkers.)

Companies like UPSIDE Foods, Mosa Meat, Vow, Good Meat, and many others have been leading the charge in bringing cell-cultivated proteins to market; these are meat products grown without the slaughter of a farm animal. While I won’t get too much into the details (full-scale cultivated meat post coming soon 😉), cultivated proteins essentially start with a stem cell sample from an animal (cow, chicken, etc.), and then scientists grow those cell cultures until they form a larger piece of meat! This process generally uses less land, water, and energy compared to conventional agriculture.

Fluke or Premonition?

How did Churchill conceive of such a technology in only 1931? We weren’t anywhere close to cell-cultivated protein!

Well, it probably wasn’t his original idea. His inspiration likely came from the famed birth of tissue engineering in the early 20th century, often attributed to the work of French biologist Alexis Carrel.

The field of tissue engineering involves using cells, biomaterials, and biochemical principles to study tissues like skin, heart, brain, and muscle. But the applications aren’t just medical—we can use tissue engineering principles in food, too! Cell-cultivated protein is a modified version of tissue engineering; instead of growing 3D tissues to study wound healing or drug delivery, we can use them to make meat.

Carrel’s famous contribution to tissue engineering was his immortal culture of chicken liver cells. What is an immortal cell culture?

Most cells are not immortal. Imagine you start a cell culture with one cell; you give it plenty of fresh nutrients to grow, grow, and grow until it divides to make two cells. Then those two cells keep growing until they divide and make two cells for a total of four. The process repeats until you have a Petri dish with millions of cells after just a few days.

But that first cell is still dividing, too! It doesn’t stop after the first division. It continues to divide, divide, and divide until it starts to act…funky. Soon, it doesn’t divide quite as quickly, it changes shape, and ultimately dies. After a while, your whole culture starts to die—the cells have reached their dividing limit!

Carrel managed to avoid this process by keeping the same cell culture alive for over 20 years, the first documented observation of an immortal cell line. TWENTY YEARS! 20! Read that again! The average lab cell culture is only kept alive for a few weeks at most!

Well, it might not have actually been so impressive. Many scientists years after this experiment have questioned Carrel’s observations; he may not have been truthful or his employees may have continually replenished the culture with fresh cells to make it appear immortal. Regardless of the integrity of his experiment, the concept still marks the beginning of tissue engineering.

Immortalized cell lines are absolutely real, though! Many biomedical scientists have observed spontaneous immortalization in mammalian and fish cells, though we still don’t understand what causes the immortalization. The most famous immortal cell line is the HeLa cell line, named for Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman who was treated for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins in the 1950s. Unfortunately, her cells were taken without her consent, and the thousands of scientific discoveries that use the HeLa cell line often fail to address the unethical isolation of her cells. Even Johns Hopkins’ official statement contains no apology or reparations to her and her family. I invite you to read more about HeLa cells and scientific consent here.

That’s it for the timeline, for now. We’ll pick up with the 1985 release of Quorn mycoprotein—the most intellectually mind-blowing alternative protein of our time, in my opinion!

If Winston Churchill predicted anything culturally accurate about the year 1981, I would sell all of my material belongings and become a Himalayan monk. I cannot emphasize this enough: Winston Churchill had no business trying to pinpoint the significant advancements made by 1981 specifically. I cannot imagine him looking at the neon leg warmers and never-ending sea of velvet that was 1981. Though, I hope his ghost both witnessed and played the first release of Donkey Kong.

Fascinating stuff. I’ve read quite a bit about this throughout the years and it continues to fascinate me. Some people seem to be against cultivated meat, even outright horrified, but I think it’s a brilliant solution if we manage to make it work on a massive scale.

As an ignorant observer, I'm intrigued. Thank you for your writing!