What's a PhD?

No really, what is it?

Happy New Year, Trash Talkers!

Having finished my first semester of grad school, I figured I’d reflect on my journey and get into the nitty-gritty of what it means to study for a PhD. What is a PhD, anyway?

A Helpful Visual

Matt Might, a professor in Computer Science at the University of Alabama Birmingham, created The Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D. to explain what a PhD is to new and aspiring graduate students. [Matt has licensed the guide for sharing with special terms under the Creative Commons license.] It’s a simple visualization of what pursuing a PhD contributes to the global wealth of knowledge because it’s much easier to draw in pictures than to say in words.

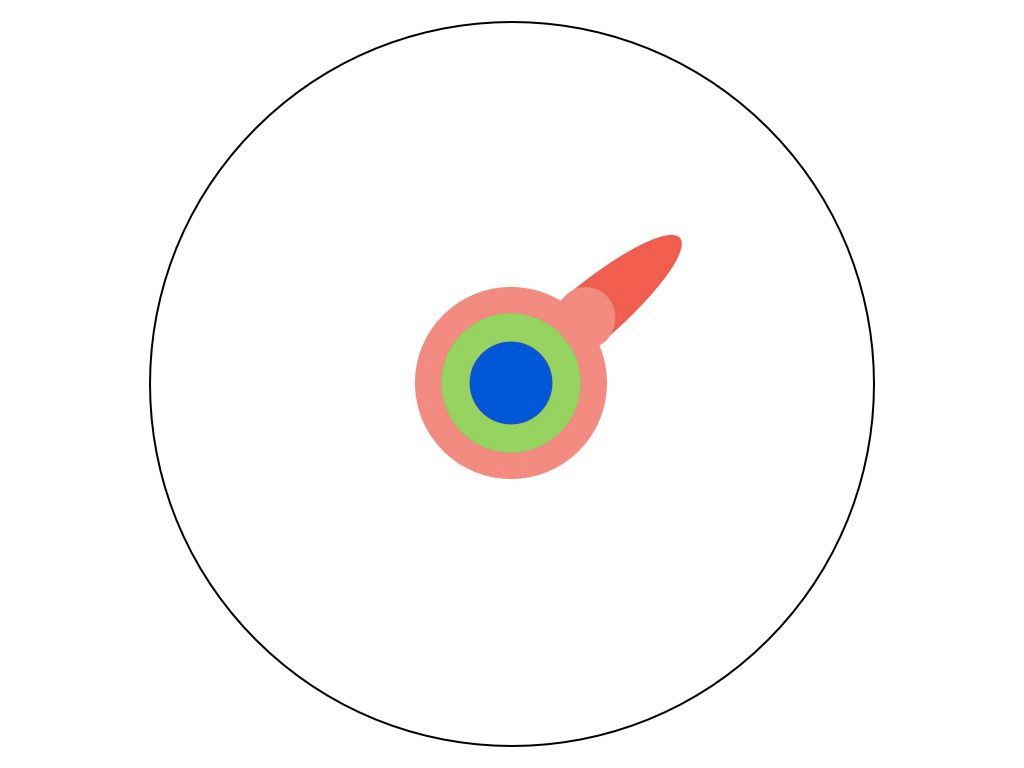

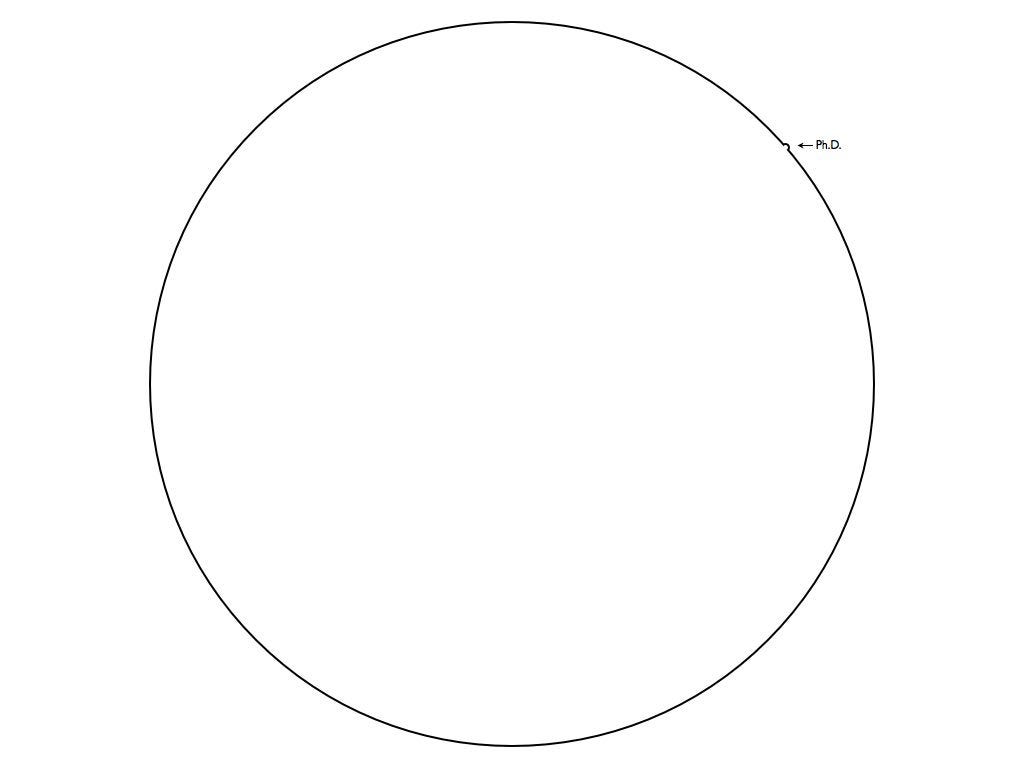

Imagine a circle that contains all of human knowledge:

By the time you finish elementary school, you know a little:

By the time you finish high school, you know a bit more:

With a bachelor’s degree, you gain a specialty:

A master’s degree deepens that specialty:

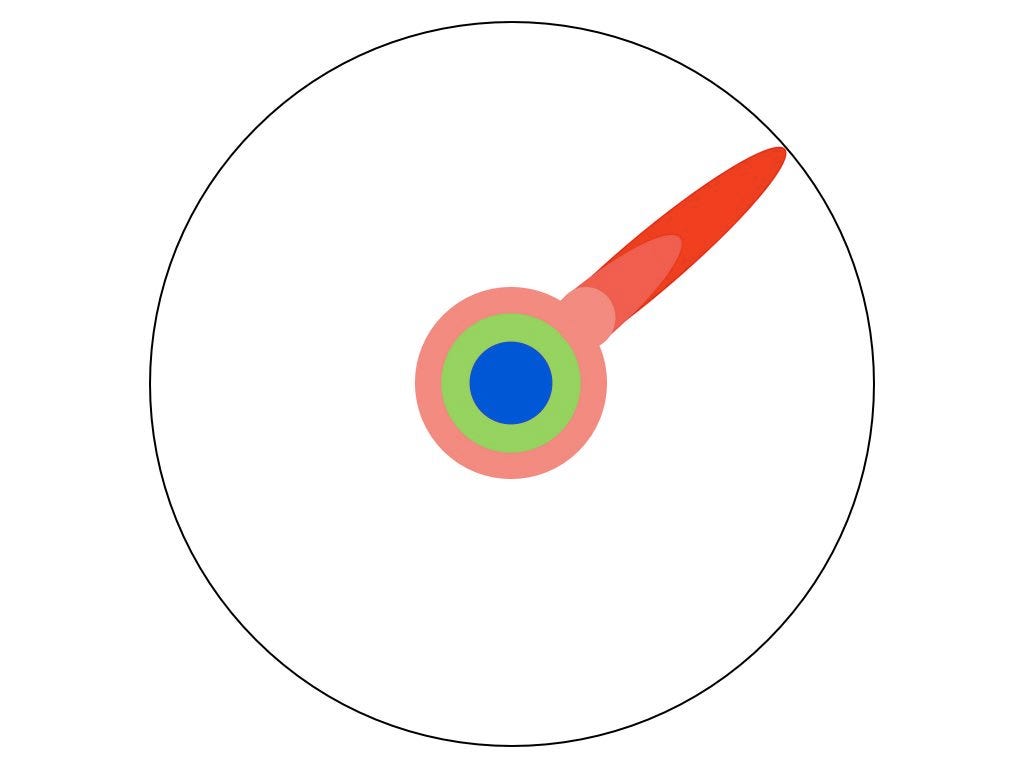

Reading research papers takes you to the edge of human knowledge:

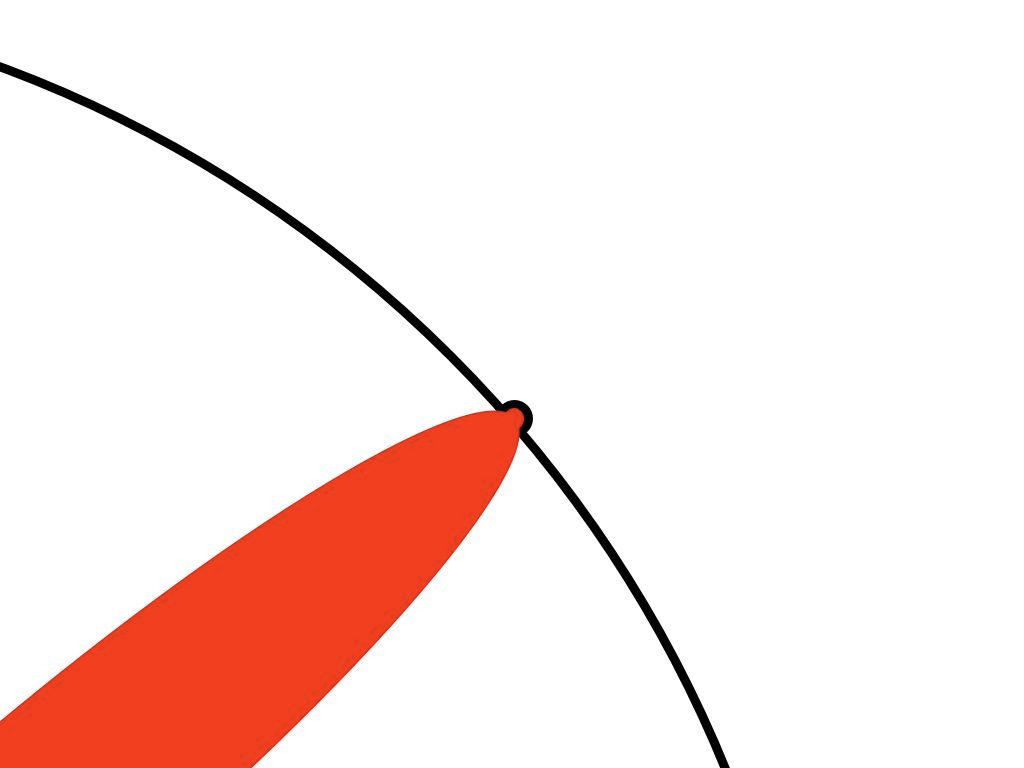

Once you’re at the boundary, you focus:

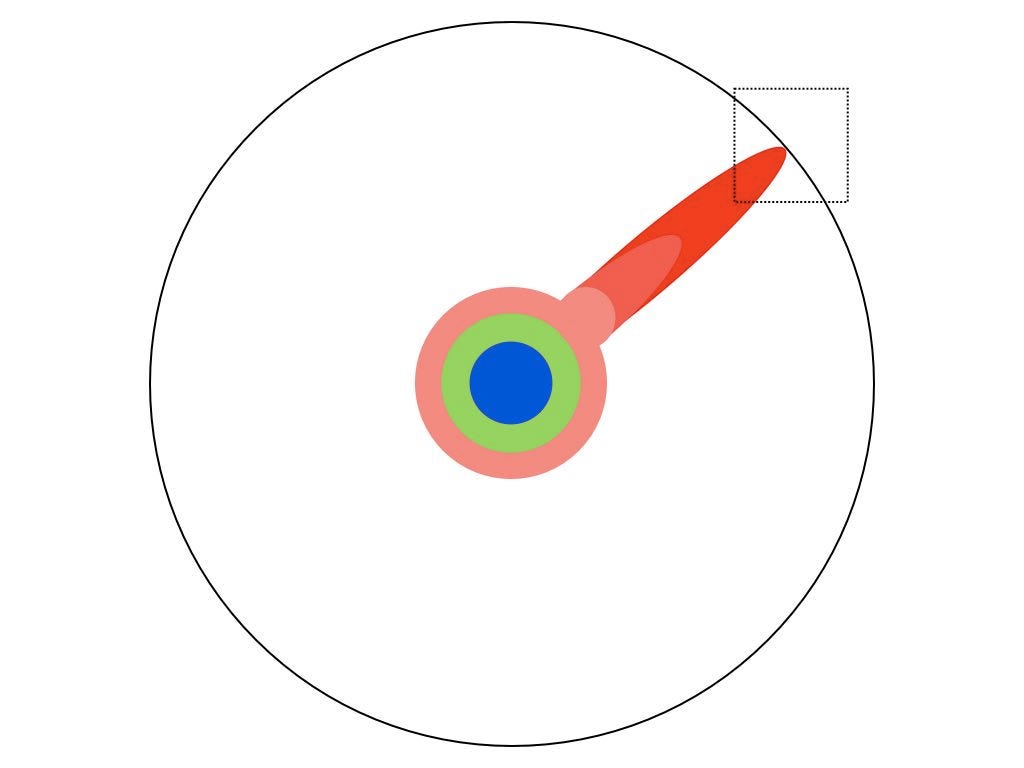

You push at the boundary for a few years:

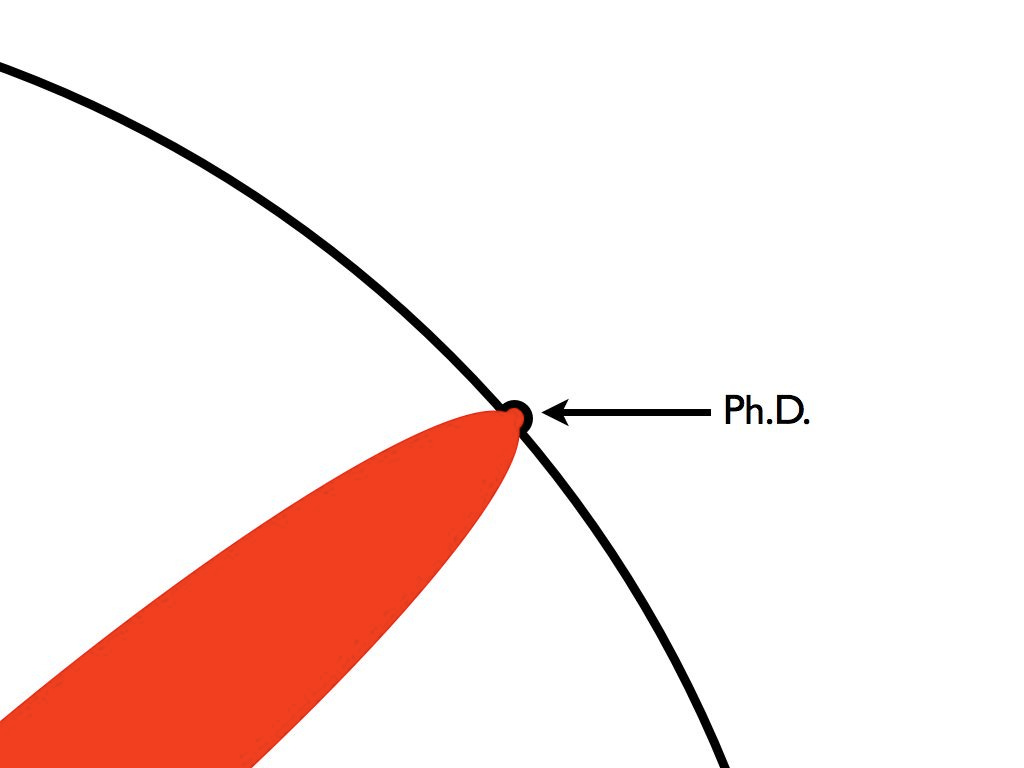

Until one day, the boundary gives way:

And that dent you’ve made is called a Ph.D.:

Of course, the world looks different to you now:

So, don’t forget the bigger picture:

Keep pushing.

PhDs & Isolating

This model caught on very quickly on several social media platforms, and now Might provides PowerPoint, Youtube, and print versions of the drawings. He advertises it as a great gift for a recent PhD graduate or someone just starting their grad school journey.

I think what this visual does best is illustrate the “boundary-pushing” of a PhD. I completely empathize with and understand that I’m studying something that nobody else on the planet is studying in the same way. This is easily >90% of my motivation for coming to work.

There are two potential pitfalls of this series of drawings: 1) the fear factor and 2) the faulty depiction of specializing.

Pushing at the boundary of human knowledge may sound like a solitary activity when it isn’t. This can instill a pretty strong sense of impending doom for young students.

How am I expected to discover something completely novel?

Am I supposed to do this alone? Who can I rely on?

In the first few weeks of my starting at Penn State, a professor warned my class about doing science in isolation (partially as an excuse for us to work on homework together); 100 years ago, science may have been done by a single man hunched over a lab bench for days on end, until he left his hovel to announce a discovery to the world. But science isn’t like that anymore. Science is done in partnership, in collaboration. Otherwise, it doesn’t get done.

So, while pushing the boundary of human knowledge is primarily the responsibility of the student, it doesn’t mean it is only performed by the student. It takes a village to do a PhD.

Specializing

When I was putting together my applications for grad school, I was under the impression that what you studied and researched in your Master’s and PhD programs was what you would study for the rest of your career (if you chose to stay in academia). I read many, many faculty profiles that all detailed the same journey:

“In my PhD, I studied [material or process]. In my postdoc, I expanded on that by manipulating [material or process] in a different way. Now, as a professor, I continue to manipulate [material or process] and adapt it to different applications.”

I understood this to be a formula that every academic followed. Start research on a thing, continue researching the thing, continue researching the thing, eventually retire.

This is not how it works AT ALL. To my (and your) delight.

Academics are constantly pivoting in their research—that’s what keeps the funding and students coming in. Many professors in my department, including my advisor, have made major pivots in their research directions over the years. Some have even switched fields to find a career niche better suited to their interests and expertise.

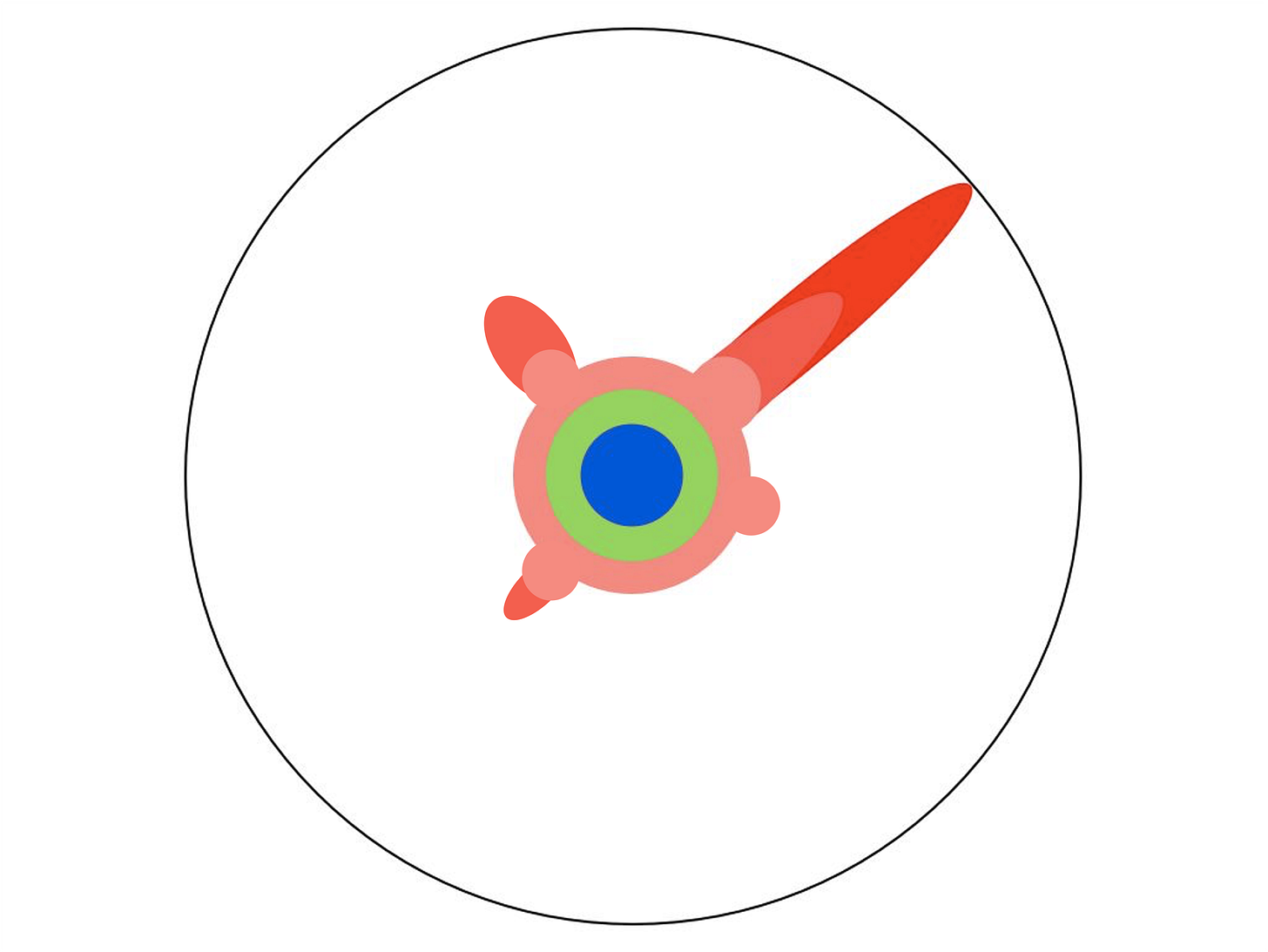

So, while the PhD is intended to create specialists, it doesn’t mean you’ll specialize in the same thing for your whole life. I’ve learned so much from my peers, hobbies, the media, art—yes, I specialize, but I am a lifelong student.

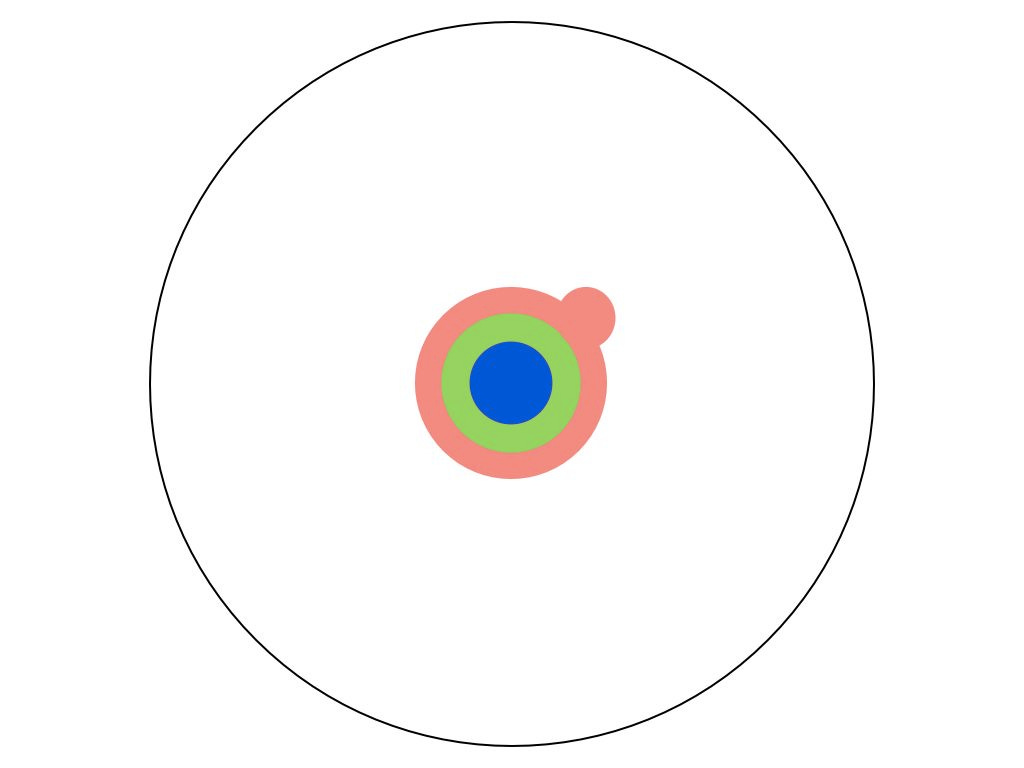

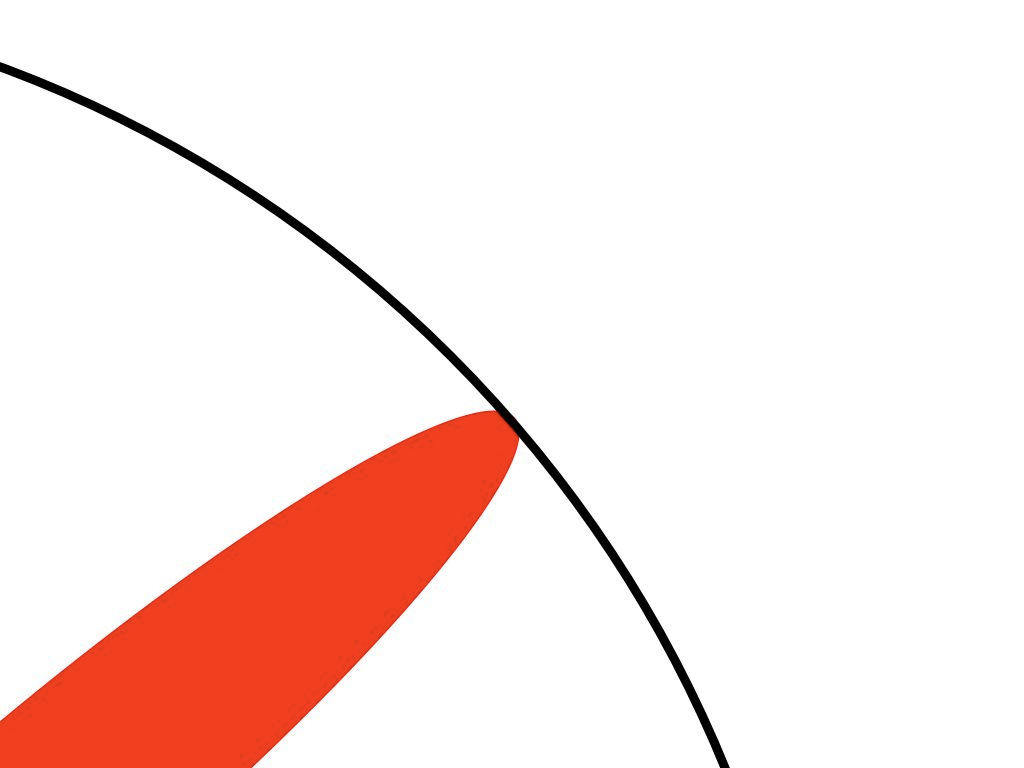

I wish Might had included an alternative version of his specialization drawing; many people have diverging expertise and interests, and not all knowledge is gained solely from higher education. His final drawing might be more inclusive and accurate if it looked something like this:

What Do You Do All Day?

To those outside of grad school, getting a PhD may sound ambiguous or confusing. A lot of people seem to think I’m just doing my undergraduate work again, in a different discipline. The main distinction between a graduate student and an undergraduate student is that graduate students are employees.

So what do I do all day at my job? Keep in mind that this is from a STEM PhD's perspective, but the formula is largely the same across fields.

PhD students have three main responsibilities:

Work on your research project. This is expected to take the majority of your time. Reading publications, planning and performing experiments, analyzing data, applying for grant funding (to do more experiments), publishing your work in peer-reviewed journals, and writing your dissertation. The main point is that this responsibility, by itself, is an entire job. Probably two jobs.

Take classes to complete your degree requirements. This is the same as undergraduate coursework, but graduate courses are generally more in-depth, of higher complexity, and applications-focused. Sometimes, you take undergraduate courses if the course content is valuable for your project. The total number of credits required for PhDs varies from school to school. I’m expected to take about 25 credits (8-9 classes) in the first 1-2 years of my degree. I’ve known students in other programs who took more classes, and some who took fewer classes. This, by itself, is an entire job.

Teach. Almost every PhD program requires assistant teaching in some capacity. Some programs require that PhD students teach a class every semester, other programs might require every other semester, or even just teach if you’re in between sources of funding. The workload of TAing depends on the course you get assigned and the professor you’re working with. This, by itself, is also an entire job.

While these are the explicit responsibilities of each student, there are many implicit ones: lab management, seeking out professional development opportunities, attending trainings, traveling to and presenting at conferences, mentoring undergraduate students, and working on side research projects. It’s easy to see how grad students’ schedules fill up quickly. We wear a lot of hats!

That’s what drew me to apply for a PhD in the first place. Mentally, I require a lot of forms of stimuli to stay engaged with my work. It’s amazing that I can take breaks from some responsibilities to work on others and then come back to them later. It keeps me awake, thinking, and motivated.

How Do I Know a PhD is Right for Me?

I’m not giving advice. Just sharing my experience. The justification for a PhD is different for each and every person.

I know a PhD is right for me because I’ve become frustrated by how much time my classes take away from my research. I love in-class learning, but man, it is so much more boring compared to my project. This is a bit of a silly reason, but it’s an indicator that I belong in research (though I’ll always be a student to some extent).

I know a PhD is right for me because I get excited thinking about where my project will take me. What new techniques will I learn, who will I collaborate with, and what will I contribute to the field?

I know a PhD is right for me because I feel at home amongst other scientists. I recently traveled to Austin, TX to collaboratively address food safety challenges with other cultivated meat experts. While I was nervous as an early career professional in alternative proteins, my apprehension settled as soon as we got to talking about science and the future of the field. I was meant to do this. I was meant to be a scientist.

In essence, a PhD is the ultimate demonstration of someone’s ability to critically evaluate our current understanding of a topic and subsequently contribute new knowledge to deepen that understanding.

Thank you!

Learned a lot from this post!