This morning, my eyes glossed over a strange LinkedIn post by an employee at Colossal Biosciences stating that they had genetically “revived” the long-extinct dire wolf species, Aenocyon dirus.

I didn’t think anything of it this morning—I thought that, at best, Colossal Biosciences had recovered the dire wolf genome from a fossil.

In the few hours since I saw that post, my entire feed has blown up with headlines. Dire wolf resurrected. 10,000 year-extinct species revived. Colossal Biosciences brings back the dire wolf. Game of Thrones is real.

Let’s discuss, Trash Talkers. Maybe we’ll even talk some trash.

Who is Colossal Biosciences?

Colossal Biosciences is a biotechnology company based in Dallas, Texas. Their primary focus is to facilitate “de-extinction,” or what the rest of us might peg as wildlife conservation. They want to prevent major biodiversity loss on our planet, especially as our climate changes and threatens vulnerable species. That’s a noble cause; Earth’s biodiversity has both intrinsic (perhaps an animal’s right to life) and extrinsic value (how we interact with animals and what services they provide our ecosystem, like beavers building dams or chickens laying eggs).

Where they lose me is the ultra-techno-futurized language and aesthetic. Let’s take a look at their website.

The landing page is an incredible feat of graphic design. Short clips of snow-white dire wolves trotting in the forest, scientists handling samples in the lab, scenic forest foliage (from the POV of prey, might I add), and other “aesthetic” shots alternate in a looped video. Right in the middle, some text:

“The science of genetics. The business of discovery.”

Wow. We don’t have time to unpack all of that.

If we scroll down, we see various collages of different animals overlayed with text akin to futuristic computer output or code. Lots of messages about the pressing need to protect extinct and critically endangered species.

Scroll farther down, more interesting images. I actually really like this one—zebras, deer, giraffes, bears, and fish amble (or swim) along a picturesque fossil or maybe a winding path of rocks.

Ah, the wonderful “Wikipedia defines this term as” tactic. Webster’s dictionary defines wedding as the fusion of two hot metals, for any Office fans. Here’s where we get to Colossal’s major claim: that they can make something de-extinct. De-extinction of course, is the process of creating something that looks like or actually is an extinct animal.

“Revival” of the Dire Wolf

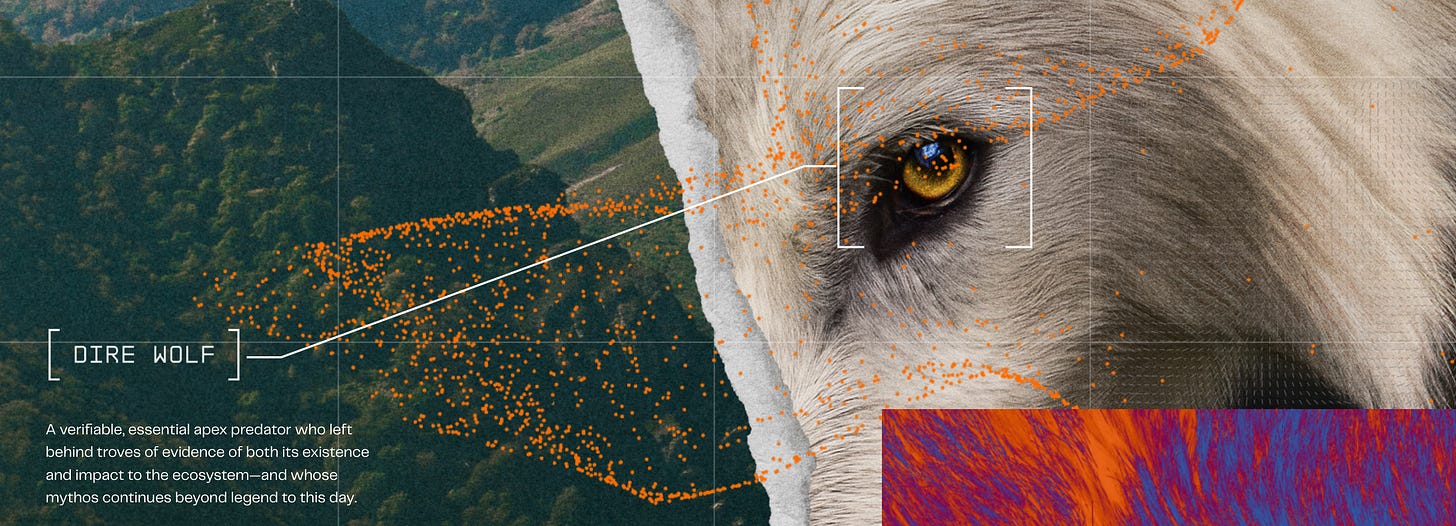

Through genetic engineering, Colossal Biosciences claims to have revived the long-extinct dire wolf. According to their website, Colossal states that there were only two samples of usable dire wolf DNA in the entire world: a tooth, and a 72,000-year-old skull. They isolated DNA from these samples and sequenced the entire genome—essentially all of the written instructions that make the dire wolf what it is. Sequencing is a very common genetic tool; we sequence bacteria, yeast, mice, and other organisms in research all the time. It’s harder to sequence genomes for macroscopic life because they have more genes. For example, the Human Genome Project was a long-time effort to sequence the entire human genome, spanning over 13 years of work.

Your genes make you. The dire wolf genome makes the dire wolf.

(In this video, they say that it’s “incredible” to generate an entire genome for a species. I would argue it is not incredible. Maybe it is more resource-intensive and takes more time for a mammal like a wolf, but it’s not far-fetched from my limited knowledge of genetics.)

So, now they’ve got the genome of the extinct dire wolf. How do you make a physical dire wolf?

Colossal’s strategy is to “map” the dire wolf genome against a close living relative, the gray wolf. If you can take a set of genes that are already pretty close to your genes of interest, you can make small edits until you have a genome resembling the sequenced genome. You take the gray wolf and make genetic changes (Colossal claims they make hundreds of edits at a time) until you have what you believe to be a dire wolf.

They don’t do this part with actual wolves, by the way (and you reasonably couldn’t do that). They make genetic changes to gray wolf cells in little plastic Petri dishes.

Then comes the “making a dire wolf” part. If you remember Dolly the sheep—the first cloned animal—this process is technologically the same. Scientists at Colossal stick a dire wolf cell inside an egg cell from a gray wolf or even a domesticated dog, which makes a dire wolf embryo. Then, the embryo is inserted into a surrogate dog, and a few short months later, dire wolf puppies.

I’ll admit—they are quite cute: Romulus and Remus are six months old, and Khaleesi is three months old:

You can even track their development on Colossal’s website.

Pretty stunning animal.

What are the Implications?

I’ll admit I’m known to have intense knee-jerk reactions to news like this. I’m generally skeptical of efforts that attempt to play God beyond a reasonable amount. Genetic modification of corn, soy, and canola are already widespread—I have no problem with those. But reintroducing a long-extinct species for (what I believe to be) an indefensible reason doesn’t cut it for me.

Colossal claims they do all of this to correct humanity’s past, current, and potentially future mistakes. If we were responsible for the extinction of a species or harmed their wellbeing, Colossal believes we have a duty to fix it. That’s a pretty easy position to stand in. We messed something up, we should fix it.

But what does “fix it” mean? Why do we have the right to reintroduce species or pretend we even know how to? Even Colossal admits that their technologies rely on our still-changing understanding of fundamental biology; for example, can we identify specific genes that make something a dire wolf versus a gray wolf? They already share a lot of similarities—how do we know which ones are responsible for their differences? And, are we certain that those genes don’t affect other traits, too?

On a macroscopic scale, what if we introduced a previously-extinct animal into an area it wasn’t fit for? Or worse, what if it was overly fit and wiped other keystone species out of the area? For species that have been extinct for a long, long time like the Dodo bird, woolly mammoth, or the dire wolf (coincidentally, all species that Colossal is focused on reviving), it’s difficult for us to predict what ecological niche they fill. What habitat, what food web, what ecosystem do they fit into if the rest of biological life has evolved without them? Save for the last blip of evolutionary time where humans have made quite a dent in the Earth, organisms become extinct because they cannot survive. Unless something about the organism or its place in the ecosystem has substantially changed, it will not survive. Things do not re-evolve back after extinction.

Hearts & Elbows

There’s a famous question in biology:

Why doesn’t your heart grow on your elbow?

It might seem absurd—of course your heart is meant to be inside your body, protected from the elements, central to your veins and arteries to maximize nutrient delivery. And we know that that makes sense. Your organs need to be in the specific places they are, or things get wonky. But how does your body know where to put the heart, hair, teeth, and fingernails?

I find this video by Hank Green best explains the sheer wonder of the human body and our somewhat limited understanding of how it came to be:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

“Where everything knows where to stop and what to be” is the best way I have thought to put it. We are made up of billions and billions of tiny evolutionary decisions (a more accurate but less wondrous term would be “evolutionary probabilities”) over an extraordinary length of time.

I’ll invite you to apply Hank Green’s whimsical sentiment to Colossal Biosciences and their dire wolves. How will we know where to stop and what to be?

What pokes my skeptical brain is breathless repetition of press releases as if they were an accurate portrayal of scientific advancement. Marketing has a vested interest in exaggerating claims. All press releases are marketing.

They haven’t brought back a dire wolf. They have created, through gene editing, a grey wolf with a few dire wolf characteristics. Interesting, but not de-extinction. It reveals little beyond the intellectual exercise of thinking about the implications. There is also the danger that through such an intervention they will create a fertile breeding ground in the unique immune systems of novel animals related to extant species for novel virus mutations that could rampage through unprepared populations.

Humans and grey wolves outcompeted dire wolves 13,000 years ago. We don’t have every detail of that extinction, perhaps their pelts became highly desired, maybe climate change, maybe human pressure on their food sources, or some combination of all these things. The utility of this is in broader understanding of further and more complicated gene editing. We’re not going back, and I don’t know how wise it is to go much further without really understanding more about epigenetics and proteomics.

Yes this free enterprise de-extinction business is much in the news today. You just gave an excellent analysis and I sent it over to BlueSky where it can get more readers perhaps.

Just because we have the bii-tech to this kind of thing doesn't mean we should do it. Can doesn't imply ought. But we so often seem to think it does. I urge great caution.